|

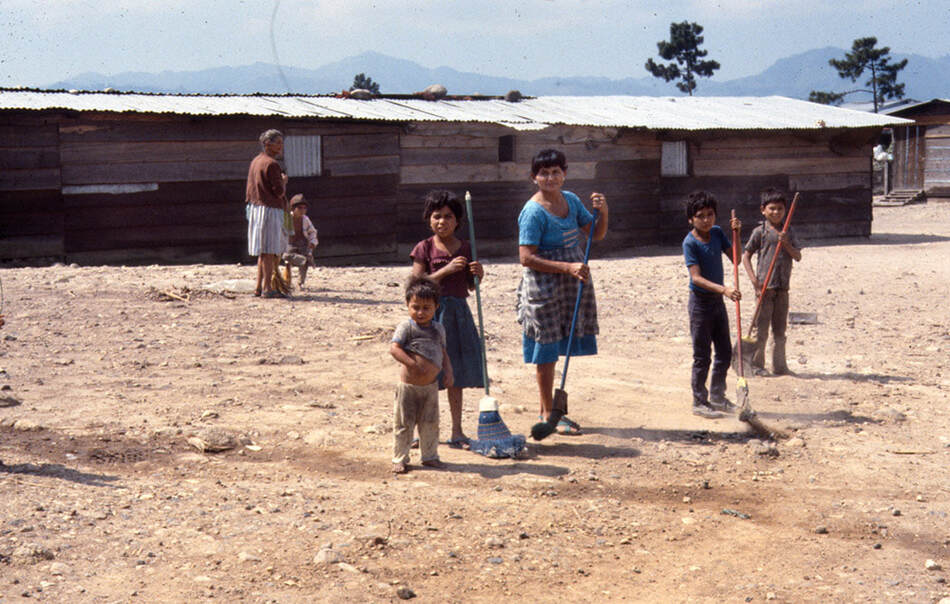

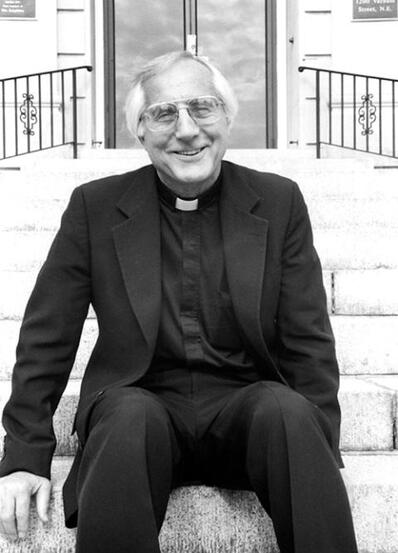

Forty-one years ago, I met Tom Gumbleton at a peace symposium sponsored by the Sacramento Diocesan Justice and Peace Office headed by former Maryknoll Sr. Georgia Lyga. Hundreds of mostly lay men and women packed the church auditorium. Tom spoke on the landmark 1983 U.S. bishops' pastoral letter on war and peace, the threat of nuclear annihilation, and the immoral costs of the military industrial complex. I had just returned from El Salvador as a member of the SHARE Foundation board, and spoke about El Salvador, the U.S.-sponsored wars ravaging Central America, the influx of refugees in the United States and the emerging Sanctuary Movement — sharing the moral (and legal) imperative to provide safe haven to those fleeing war and to stop U.S. intervention. Tom was 53 years old. I was 28. It was the beginning of a deep friendship and partnership in the struggle for peace with justice in our world. I quickly discovered that Tom was cut from a different cloth: a bishop who not only listened (and listened deeply) to me, a young woman in the church (a radical act then as now) — but one who made decisions based on deep reflection and study, guided by the social Gospel, the prophetic tradition and the lived experience of those he accompanied. A rare trait indeed. Tom's choices were deeply pastoral decisions. He gravitated to those who suffered the violence of war as well as structural violence of economic and political models that excluded the vast majority of the world's people. He was inspired by Martin Luther King Jr.'s vision of the beloved community and commitment to nonviolent direct action. Tom, who died April 4, 2024, at age 94, used his office and position unlike any other to give voice to those he saw as sisters and brothers who were ignored and/or oppressed. He said yes to countless invitations to examine the root causes of world events, to place his hand in the open wounds of those who suffered, and to challenge the complicity of his country and church, even when doing so placed his standing in his country and the institutional church at risk. Tom understood Dietrich Bonhoeffer's "cost of discipleship." He was inspired by Salvadoran Archbishop St. Óscar Romero's recognition that "If they kill me, I will rise in the Salvadoran people." He was a peacemaker in word and in deed. His solidarity with the peoples of Central America provides a window into his approach and his courage. Not long after we launched the Sanctuary Movement on March 24, 1982, the second anniversary of Romero's death, Tom supported the movement when only a handful of bishops did (including Archbishop John Quinn in San Francisco) and when the U.S. bishops' conference cautioned bishops against declarations of sanctuary. Tom challenged U.S. foreign policy not only in El Salvador and Guatemala, but in Nicaragua, where the U.S. illegally armed and supported the Contras. In 1987, when I was executive director of the SHARE Foundation, Tom accepted our invitation to join the steering committee of SHARE's "Going Home" Campaign. The task: to accompany 10,000 Salvadoran campesinos who had been forced to flee their homes amid saturation bombings and who longed to return to their villages after living in the confines of refugee camps in Mesa Grande, Honduras. The U.N.-sponsored camps were located on a remote, expansive flat space, dotted with hundreds of temporary tents erected on a dusty, chalk-like surface surrounded by a cyclone fence perimeter and patrolled by the Honduran military. Months of displacement had turned into years. The repatriation was not supported by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, which deemed repatriation as too risky since the refugees' homes of origin were in "zones of conflict." The Salvadoran and Honduran governments and militaries opposed the repatriation, as did the U.S. government and U.S. military advisers. But the Salvadoran refugees were determined. They made a direct appeal to the SHARE Foundation and the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment to accompany them in what became one of the largest nonviolent direct actions of the war — a movement to repopulate their homes, cultivate their lands, and reclaim the peace by their presence. In short, to stop the bombs. They invoked the Exodus story — a people of faith defying Pharaoh (the Salvadoran military) by organizing the beloved community with the strength of Moses (Romero) as wind upon their backs. We at the SHARE Foundation were determined to meet in person with the refugees themselves, in Honduras. This was just one of the many times Tom said yes to join us in the endeavor. He braved the trip to Mesa Grande with me and the Rev. John Moyer, the executive director of the Northern California Ecumenical Council. We rented a car at the airport and wound our way to Mesa Grande on unpaved roads. By the time of our arrival, we were met with one hurdle after another to secure the required permits to gain entry to the camp. We were buoyed by the support of Salvadoran Lutheran Bishop Medardo Gómez and the head of Diakonia, Dimas Vanegas, who traveled from El Salvador to meet us outside the camps. Even then, the military authorities imposed a late requirement to secure the written support of the local Honduran bishop before granting us access to the camps. The new condition required a nighttime drive to the town where he lived — a good distance away under a threatening storm. After surviving a torrential downpour and lightning strikes on those same unpaved roads back to the bishop's town, we found the bishop at a private party. Though he took time to meet us, he initially questioned our credentials until Tom flipped into Latin to convince him of our bona fides. We returned to the refugee camp the next day, with the bishop's signed letter of support in hand. We gained entry and met with the refugees' leadership and hundreds of refugees under pelting rain. Tom listened, expressed our solidarity and won their hearts. And, of course, they won his. With Tom's unwavering support, over the next two years, the SHARE Foundation and the Interfaith Office on Accompaniment organized religious delegations to accompany more than 10,000 men, women and children through four successful repatriations. Throughout that effort, U.S. and Salvadoran authorities sought to intimidate and undermine those of us active in repatriation — especially Tom. But their tactics failed.

Not long after, SHARE sponsored a 14-city us tour by Jesuit Fr. Jon Cortina, who spent years working to find children missing after El Salvador's civil war. Tom and the Detroit Central America Committee hosted Jon to promote support for the repatriated communities rebuilding their lives. In my introduction of Father Jon, I shared that, in El Salvador's repopulated communities, when people are asked about Romero, they say, "He's alive. He lives in Detroit" — a reference to Bishop Tom Gumbleton. For years after the Salvadoran Civil War ended in 1992, Tom continued visiting communities there, accompanied by his longtime confidant, partner and president of the SHARE Board, Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Sue Sattler; Bill and Mary Carry; and Oscar Chacón. Tom joined in the annual protests at the School of the Americas. He visited communities on the U.S.-Mexico border. He was a founding member of Pax Christi USA in the context of the Vietnam War and amplified his peace work in Haiti, in Iraq and across the globe. In 2015, on the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the killings of four U.S. church women in El Salvador, Tom joined a delegation co-sponsored by the SHARE Foundation and the U.S. Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR). José Artiga, by then executive director of the SHARE Foundation, led the group. Seventy-five women religious, laywomen and a few men made the pilgrimage to mark the ultimate sacrifice of Maryknoll Srs. Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, Ursuline Sr. Dorothy Kazel and laywoman Jean Donovan, and all those who died during the war. Tom supported them at the same time the Vatican was completing its appalling investigation of U.S. women religious in general and LCWR in particular. Tom's capacity to empathize and bear witness to human suffering was matched by his ability to find joy in the resilience of the human spirit in the most hopeless of circumstances. Despair was not an option. Tom was a source of profound hope for the communities with whom he worked. He, in turn, was nourished by their love and courage. We give thanks for the life and love of our brother — a beautiful priest, a dear friend, a brave and compassionate heart, a brilliant mind, a rare leader who used his position to advance authentic peace and justice. Published in the NCR: https://www.ncronline.org/opinion/guest-voices/tom-gumbleton-was-bishop-cut-different-cloth His light shines forever!

Tom Gumbleton, PRESENTE! 8 de marzo - Día Internacional de la Mujer Cada ocho de marzo se conmemora el día internacional de la mujer, un día para reivindicar el derecho de las mujeres a vivir una vida libre de violencia y en igualdad de oportunidades. En El Salvador lamentablemente se está viviendo un retroceso en el reconocimiento de los derechos de las mujeres, la normativa jurídica que fue conquista por varios años de lucha, es una de los principales logros de las mujeres que está siendo afectado. El caso de la “Ley de Igualdad, Equidad y Erradicación de la Discriminación contra las mujeres” – LIE, aprobada en 2011, establece los mecanismos para que el estado asuma la responsabilidad de implementar acciones para que las mujeres tengan igualdad de oportunidades, acciones que hoy en día se ven afectadas por la decisión del gobierno actual de prohibir la implementación de la educación en igualdad de género en los Ministerios de educación y salud, así como en varias dependencias de estado; y con la reducción de municipios se considera que cerraran las unidades de genero creadas en las municipalidades, que son las encargadas de implementar dicha ley.  Otra de las amenazas a los logros alcanzados por las mujeres es el limitado acceso a la salud, el desempleo, los desalojos de la tierra, la falta de apoyo para la producción, además de los efectos del cambio climático que amenaza la alimentación de las familias donde las mujeres son la cabeza del hogar y la principal proveedora de los servicios a la familia. Como Fundación SHARE nos solidarizamos con las mujeres de El Salvador y Honduras y las acompañamos en sus justas demandas para la reivindicación e igualdad de sus derechos. Saludamos a las organizaciones de mujeres que a diario se organizan y luchan por mejorar su calidad de vida, la de sus familias y la conquista de la igualdad de derechos. De igual manera, en este mes de marzo queremos recordar y conmemorar la siembra de Berta Cáceres, un símbolo de lucha para las mujeres en Honduras, quien nos enseñó a unirnos en las diferentes luchas en defensa del medio ambiente; y para mejorar las condiciones de vida de la población de la región. Por último, llamamos a la solidaridad internacional a estar atentos al que hacer de las mujeres de las comunidades rurales y de las mujeres defensoras de derechos humanos de las organizaciones sociales. Les invitamos a sumarse a nuestras campañas de apoyo para el bienestar de las mujeres, una muy importante es la campaña Sembrando Semillas de Esperanza para la producción de alimentos sanos a las mujeres de Chalatenango. Seguimos resistiendo en el espíritu de lucha de Berta, Rufina, de María Julia Hernández y muchas mujeres defensoras de los derechos de las mujeres, porque los derechos de las mujeres son irrenunciables. San Salvador, 8 de marzo de 2024

Dia Internacional de la Mujer |

SHARE EL SALVADORSHARE STRENGTHENS SOLIDARITY WITH AND AMONG THE SALVADORAN PEOPLE IN EL SALVADOR AND THE UNITED STATES IN THE STRUGGLE FOR ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY, JUSTICE, AND HUMAN AND CIVIL RIGHTS. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

SHARE El Salvador

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed